Why People Maintained Lower Body Weights in the 1970s and Lessons for Modern Life

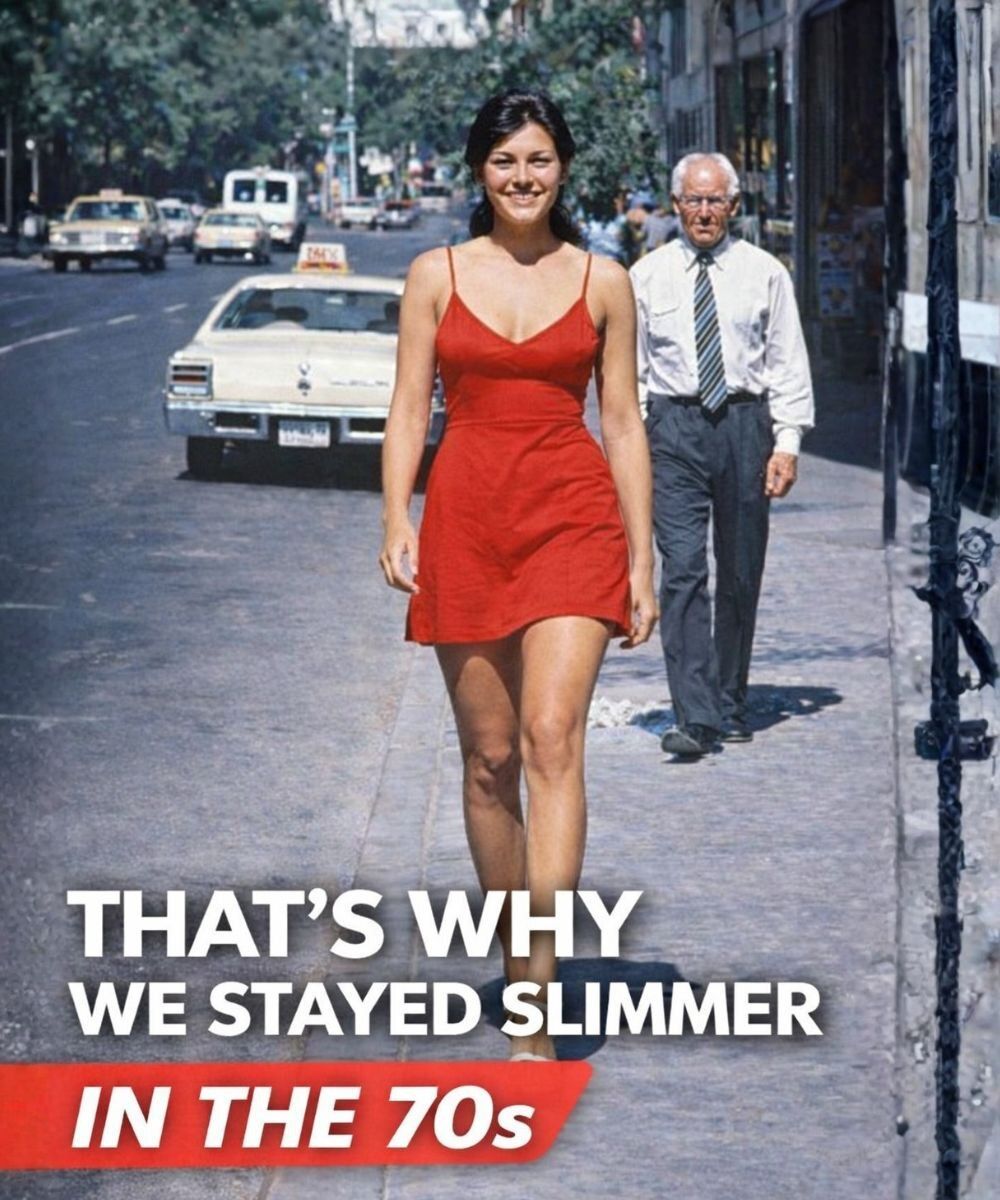

If you spend an afternoon thumbing through old Kodak prints from the 1970s—the kind with the rounded corners and the slightly faded hues—a striking observation inevitably emerges: the people in the frames look fundamentally different. From the neighbors gathered at a backyard barbecue to the coworkers in the background of an office party, there is a pervasive sense of physical balance. People appeared leaner and more naturally active. Crucially, this wasn’t a look reserved for the “fitness enthusiast” or the weekend warrior; it was the baseline for the average person. For those who lived through it, these images aren’t just nostalgia—they are a record of a different biological rhythm. The leaner frames of the 1970s weren’t the result of a secret health formula or a collective burst of extraordinary willpower. Instead, they were the byproduct of a world where health was built into the very architecture of daily life. Understanding this shift isn’t about romanticizing the “good old days”; it’s about identifying the quiet systems that once supported healthier bodies and seeing if they can be salvaged for the modern era.

Movement as a Necessity, Not a Choice

In the 1970s, “exercise” wasn’t a scheduled appointment at a boutique gym or an activity tracked by a digital app. Physical exertion was simply a requirement of existence.

With many households operating with only one car—or sometimes none—walking was the primary mode of transportation. Children didn’t just play; they roamed, spending hours on bicycles, climbing trees, and traversing neighborhoods. For adults, the day was punctuated by movement: walking to the bus stop, carrying heavy grocery bags, and navigating multiple flights of stairs.

Even the professional landscape demanded activity. Office jobs were far less sedentary, requiring employees to move between departments, stand at counters, or physically transport documents. By the time the sun went down, the average person had logged miles of walking and hours of standing—not because they were trying to “hit their steps,” but because that was how life unfolded.

The Simplicity of the 70s Kitchen

The culinary landscape of fifty years ago was unrecognizable compared to today’s high-traffic grocery aisles. Stores were smaller, and their inventory was largely limited to simple, recognizable staples: seasonal produce, eggs, milk, meat, bread, and grains.

Highly processed convenience foods—the “ultra-processed” items that dominate modern diets—were outliers. Things like prepackaged microwave meals, protein bars, and oversized sugary drinks were either non-existent or treated as rare indulgences. In this era, sugar and salt were flavorings used sparingly in the kitchen, not pervasive additives hidden in every box.

Furthermore, the act of eating required the act of labor. Cooking meant peeling, kneading, stirring, and cleaning. This intentionality created a natural awareness of nourishment. Meals were eaten as a response to genuine hunger rather than a reaction to boredom or the constant digital “pings” of a food delivery app.

The Power of Predictable Rhythms

Eating in the 1970s followed a rigid, predictable script: breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The modern culture of “grazing” or constant snacking hadn’t yet taken hold. This wasn’t necessarily a matter of self-discipline; it was environmental. Vending machines were rare, and the relentless barrage of food advertising was limited to a few television channels.

This predictability allowed the human body to regulate its own hunger and satiety cues. People ate until they were satisfied, then moved on to other activities. The body understood when nourishment was coming, which fostered a natural energy balance that today’s chaotic eating schedules often disrupt.

Portion Control by Default

In the 1970s, “portion control” wasn’t a diet strategy; it was the default setting of the marketplace.

-

The Packaging: Soft drinks were sold in small bottles, not 32-ounce “Big Gulps.”

-

The Plate: Dinner plates were significantly smaller than the platters used today.

-

The Restaurant: Servings were moderate, and the concept of the “endless refill” was a future anomaly.

Because the environment didn’t constantly push “supersized” options, people consumed fewer calories without ever having to consciously track or restrict them. Food was viewed primarily as fuel, not as a form of high-octane entertainment.

Life Beyond the Screen

Finally, the 1970s were characterized by a different relationship with technology. While television was a staple, it did not yet dominate every waking hour. Shows aired at specific times; when a program ended, the television was turned off.

There were no infinite scrolls or digital rabbit holes to fall into. Children watched a show and then headed back outside. Families sat at tables for meals without the distraction of glowing screens. This limited “screen time” meant that more of the day was spent in a state of physical or social engagement, protecting the body from the long-term metabolic consequences of the sedentary, digital life.

The 1970s body was a reflection of a world that moved at a human pace. It was a time when movement was mandatory, food was simple, and the environment naturally favored moderation—a stark contrast to the modern world where health often requires a constant, uphill battle against our own surroundings.

In an era before the smartphone became a permanent extension of the human hand, attention was a localized resource. In the 1970s, without the constant pull of tablets or social media, the human gaze was focused on immediate surroundings, face-to-face social interactions, and the outdoors.

Compared to the modern landscape, where daily screen time can easily vanish into a four-to-six-hour vacuum, the 1970s naturally mandated engagement with the physical world. This wasn’t a conscious “digital detox”—it was simply the only reality available. It encouraged movement and conversation as the default settings for human existence, creating a biological environment that modern science is only now beginning to fully appreciate.

The Stress Release Valve: Action Over Distraction

While the 1970s certainly had its share of societal and personal stressors, the nature of that stress was fundamentally different. It was intermittent, not the 24/7 “always-on” inundation of news alerts and digital demands we face today.

Crucially, the era provided healthier outlets for release. When pressure mounted, the response was often physical: gardening, a long walk, or a hands-on hobby. Stress was managed through connection and action rather than the passive consumption of high-calorie “comfort foods” or the blue-light stimulation of a screen. This supported more consistent sleep routines, which in turn stabilized metabolic health and appetite regulation—a virtuous cycle that modern life has largely disrupted.

The Physics of the Old Office

Even professional life, now synonymous with sedentary behavior, required a baseline of physical effort. In the 1970s office, “work” involved walking between departments, navigating stairs to deliver paperwork, and standing for various collaborative tasks. Manual labor was more prevalent across the workforce, and the notion of sitting for eight hours without interruption was an anomaly. Physical activity was seamlessly integrated into the workday rather than being an exhausting chore to “fit in” after a long commute.

The End of the “Snack Hack”: Boredom as Motivation

One of the most profound shifts in human behavior involves our response to boredom. In the pre-digital age, idle moments were the primary motivators for action. Without a screen to provide instant hits of dopamine, children were driven outside to explore and engage in creative play; adults turned to chores, neighbors, or tactile hobbies.

In today’s world, boredom is often the immediate trigger for snacking or scrolling. In the 70s, it was the trigger for movement. This environment promoted a natural energy balance where “doing something” was the only cure for “having nothing to do.”

Re-Engineering the Modern Environment

The people of the 1970s were not more disciplined or morally superior than us. They were simply responding to an environment that encouraged balance. To replicate those results today, we must look at environmental design rather than relying solely on willpower.

Strategies for a “70s-Style” Modern Life

We can reintroduce these timeless principles without discarding modern convenience by adopting specific, intentional habits:

-

Prioritize Natural Movement: Replicate the “accidental exercise” of the past by walking or biking for short errands, taking the stairs as a rule, and scheduling “movement breaks” to break the sedentary spell of desk work.

-

The Return of the Home Kitchen: Preparing meals from scratch using fresh, whole ingredients—vegetables, grains, and lean proteins—not only improves nutrition but adds “incidental activity” back into the day. The physical act of washing, chopping, and stirring is a form of mindfulness that fosters a deeper connection to our fuel.

-

Structured Eating and Mindful Portions: Emulate the 70s rhythm of breakfast, lunch, and dinner. By using smaller plates and removing digital distractions from the table, we can better hear the body’s natural satiety cues.

-

Digital Boundaries: Just as 1970s television was scheduled and limited, modern screen use requires firm borders. Setting screen-free zones during meals and before sleep can restore the hormonal balance necessary for weight regulation and mental clarity.

The Bottom Line: Rhythms Over Regimes

The leaner, more balanced bodies of forty years ago were not the product of a secret diet—they were a reflection of a lifestyle where social engagement, simple foods, and predictable routines were the norm.

Reintroducing these habits today is about more than nostalgia; it is a practical approach to well-being. By managing stress through connection, prioritizing sleep, and turning idle moments into creative or physical ones, we align our modern lives with the way the human body was designed to function. Sometimes, the most “innovative” health strategy is simply a reminder of how life used to work.