Devastating Canc3r Diagnosis At 44 Sparks Concern Over Sandwich Millions Eat Daily!

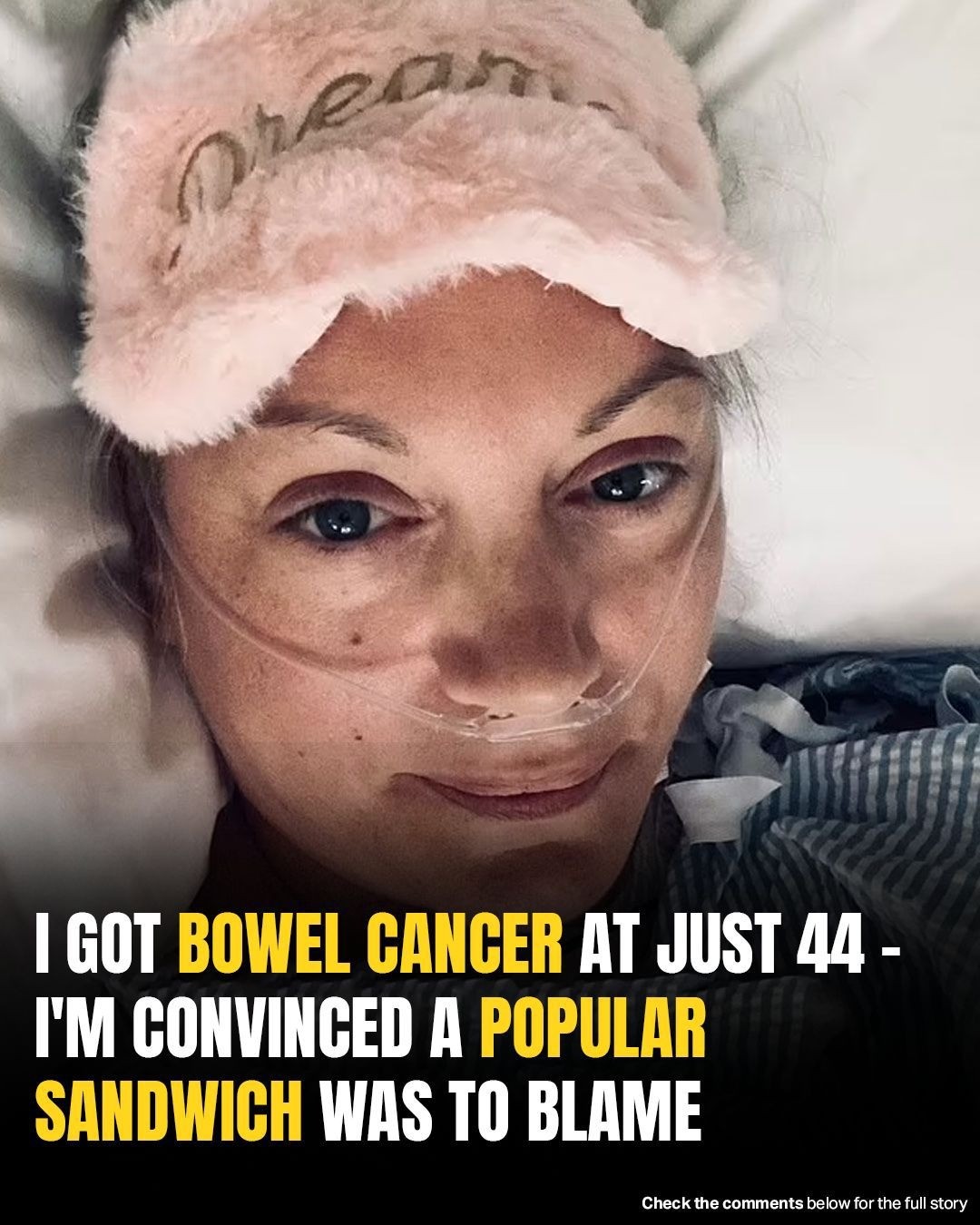

November 7, 2019. That date remains etched into my memory, marking the precise moment my life bifurcated into “BBC”—Before Bowel Cancer—and the agonizing reality that followed. A stunned, thick hush fell between my husband and me as we slowly pulled out of the hospital parking lot in Melbourne. Just minutes before, slumped forward with my head in my hands, I had listened as a highly credentialed gastrointestinal surgeon calmly delivered the validation of my deepest fears. A recent biopsy had confirmed that the large mass discovered in my colon was malignant. The grim news was compounded by a CT scan revealing the cancer had already metastasized to my liver.

“I’m afraid that means it’s officially stage-four bowel cancer,” the surgeon told us, offering a small, possibly well-intentioned, caveat before the weekend: “But… um, don’t worry, I’m pretty sure it’s all treatable.” While I would later learn that some stage-four patients do indeed defy the odds and can even achieve a cure, in that harrowing moment, the only thought consuming me was the fear that my life was measured in months, not years.

My mind began to spiral uncontrollably. Christmas was just weeks away. Was this going to be my last? My children were just nine and eleven. How would they cope? In that tempest of mental turmoil and existential dread, the only anchor I could find was an urgent need for answers, leading me to my phone and the unforgiving certainty of Google.

“What are the causes of bowel cancer?” I typed as we drove toward our home, where the devastating news awaited our children.

The search results presented a multitude of known causes and risk factors, and I meticulously reviewed each one. Was I over fifty? No. Was I morbidly overweight? Like many mothers, I carried a few extra pounds, but obese? No. Had I ever smoked? Never. Did I have a hereditary predisposition or a close family history of the disease? No. Did I maintain a diet low in fiber and high in highly processed foods? Quite the opposite; my daily meals were rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, and oats. Was I sedentary? Of course not. Did I drink alcohol frequently? Only a couple of glasses of Pinot Noir on a Friday night.

This initial review left me utterly perplexed. Why me? Why now? At forty-four years old, the typical risk profile did not align with my reality. “What the hell!” I blurted out, the sudden noise breaking the oppressive silence in the car.

Lost in my own analytical universe, I continued to search for other potential connections. To my growing dismay, I stumbled upon a recurring theme: numerous studies suggesting that the regular consumption of red and processed meats—including staples like salami, frankfurters, or bacon—significantly elevates the risk to health and life.

The strong link between processed meats and bowel cancer, along with other potential adverse health effects, wasn’t new, having generated headlines over the years. However, like many people at the time, I was not fully aware of the extent of the risk, particularly at my relatively young age.

I reflected on my dietary habits, initially reassuring myself that I didn’t consume much processed meat. I typically favored fish, cheese, or chicken over the plastic packets of pre-sliced ham. But the knowledge forced a deeper, more rigorous inventory of my past choices. I recalled the indulgence of bacon at brunch, the bits of bacon I’d frequently add to vegetable soup for flavor. As an expatriate missing my roots in Hampshire, I reminisced about the pleasure of preparing an enormous gammon leg each Christmas Eve, carefully etching the little diamond designs into the fat before slow cooking it. And the slices of leftover gammon I’d enjoy in the subsequent days were always a favorite. Then, I remembered all the times I was tempted at the local grocery store by the smell of grilled sausages wrapped in white bread.

Could the cumulative consumption of these processed meats, in an otherwise healthy diet, have been the initiating cause of my colon cancer?

I knew I could never be absolutely certain, but the possibility—that I was the architect of my own anguish, and worse, my family’s impending devastation—was almost unbearable. It would have been infinitely simpler to attribute the illness to a cause completely beyond my control.

Fueled by indignation, I delved into the scientific literature, uncovering information that I realized the multi-billion dollar meat industry would prefer to keep obscured. I was incensed, but my journalistic instincts kicked in, spurring a resolution to write a book exposing the shadowy economics of processed meat production.

I discovered an extraordinary study involving nearly half a million adults that concluded: those “with a high consumption of processed meat are at increased risk of early death, in particular due to cardiovascular diseases but also to cancer.” I gasped reading that line. Furthermore, in 2015, the World Health Organisation (WHO) classified processed meats in the same cancer-risk category as asbestos and tobacco. The WHO also stated that consuming just 50 grams of processed beef daily—the equivalent of one sausage, two slices of ham, or a few rashers of bacon—raises the risk of colon cancer by 18%.

According to Cancer Research UK, an estimated 13 percent of the 44,000 new cases of bowel cancer diagnosed in Britain each year are believed to be attributable to the consumption of these processed meats. The disease is also disproportionately affecting younger demographics in the UK, with rates among individuals aged 25 to 49 increasing by nearly 50% since the early 1990s—all while the bacon sandwich remains one of the country’s most cherished snacks.

The Problem of Nitro-Preservatives

While meat has been cured with salt for millennia, modern processing relies heavily on artificial nitro-preservatives, most frequently sodium nitrite. This chemical significantly extends a product’s shelf life, minimizes the risk of food poisoning (like botulism), and is responsible for giving cured meat its characteristic pink color. These preservatives are effective and cheap. A product like salami or bacon can boast a shelf life of up to eight weeks. However, the long-term health consequences of their consumption are often obscured or disregarded.

Sodium nitrite is a crystalline powder, similar to kitchen salt. It dissolves easily in water, is odorless, and can be injected into meat, added to mixes, or combined with water to form a brine known in the industry as a “pickle.” To my horror, I learned that this same compound is used as a food preservative, a component in car antifreeze, and utilized to prevent corrosion in pipelines. It is also found in insecticides, dyes, and medications.

Studies indicate that nitro-preservatives are not carcinogenic in their pure form. However, under specific conditions—particularly when cooked or digested—they release chemicals, chiefly nitric oxide, which react with the meat to form compounds that are highly cancer-inducing. These are known as N-nitroso compounds (nitrosamines). When we digest processed meat, the liver breaks down these nitrosamines, which can directly damage DNA and cause the mutations that lead to cancer. They are also known to damage intestinal cells directly.

Despite the clear health risks, food producers struggle to abandon nitro-preservatives. Without them, processed meats would quickly turn an unappealing brown and lose their visual attractiveness. Furthermore, the meats would need to be sold within hours, making long-distance transport and long shelf lives—the cornerstones of the industry’s profitability—impossible.

A New Lease on Life, and a Renewed Mission

Following my diagnosis, I endured a seemingly unending gauntlet of difficult treatments, including radiation, chemotherapy, and four complex surgeries. Despite these efforts, checkups revealed that the cancer was persistently returning. As treatment options dwindled in early 2024, I was offered a liver transplant—a relatively new, high-risk procedure for patients with advanced colon cancer. I knew the risk was immense, but I felt I had no choice but to take the opportunity.

I endured six agonizing months of waiting, instructed to be ready for the hospital’s call at any time. The call finally arrived on a beautiful, balmy evening last year. A precious liver, donated from another state, had arrived at my hospital via private jet. A family’s grief was about to be translated into my chance for life. Less than eight hours later, I was wheeled into surgery, releasing my husband’s hand as I went under the anesthesia. I awoke hours later, still on a ventilator, but the physicians confirmed the nine-hour procedure was successful. I no longer had cancer, and my new liver was functioning perfectly. Lying there, I silently placed my hands over my closed incision, offering a profound, wordless thanks to my donor and their family.

The months that followed were dominated by a grueling recovery, setbacks, and hospitalizations for infections. Yet, I am immensely grateful to be alive and cancer-free, even as I navigate ongoing health challenges.

Unsurprisingly, I no longer consume processed beef. I now equate the smell and even the sight of it with the physical anguish and psychological misery of cancer, making me physically ill. Neither my husband nor my children consume it anymore, either. Their initial, loud complaints about missing their favorite pepperoni pizza ceased abruptly the moment I clarified the direct link between pepperoni and cancer risk.

While it is encouraging to see nitrite-free alternatives, such as Finnebrogue Naked Bacon in the UK, beginning to appear in stores, they remain a tiny fraction of the market. Ultimately, we cannot rely on food corporations to willingly resolve this issue, as eliminating nitrites is fundamentally unprofitable for them. Instead, it is the government’s responsibility to mandate change, implement clear warning labels, and launch extensive public health campaigns.

However, consumers hold power too, by consciously reducing meat consumption and expressing an unwavering preference for chemical-free alternatives. Just as free-range eggs eventually became a retail standard, these healthier items will not become the norm until consumer demand forces the market to shift. I am fortunate to be alive, but hundreds of thousands of people die from colon cancer each year—an illness too often traceable to the processed beef in our diets. The sheer frequency of these preventable deaths is intolerable, and we must take decisive action now.